In 1931, a big Rolls rushed precious cargo from the Solent to Derby. We retrace its route in the modern equivalent, a Cullinan Black Badge

It’s summer 1931 and, since June, England has been enduring thunderstorms, flash floods and even the occasional tornado.

Thankfully, before autumn begins in September and the days begin getting shorter, there’s something truly exciting to look forward to, an event that will galvanise this rain-soaked nation: the Schneider Trophy seaplane race.

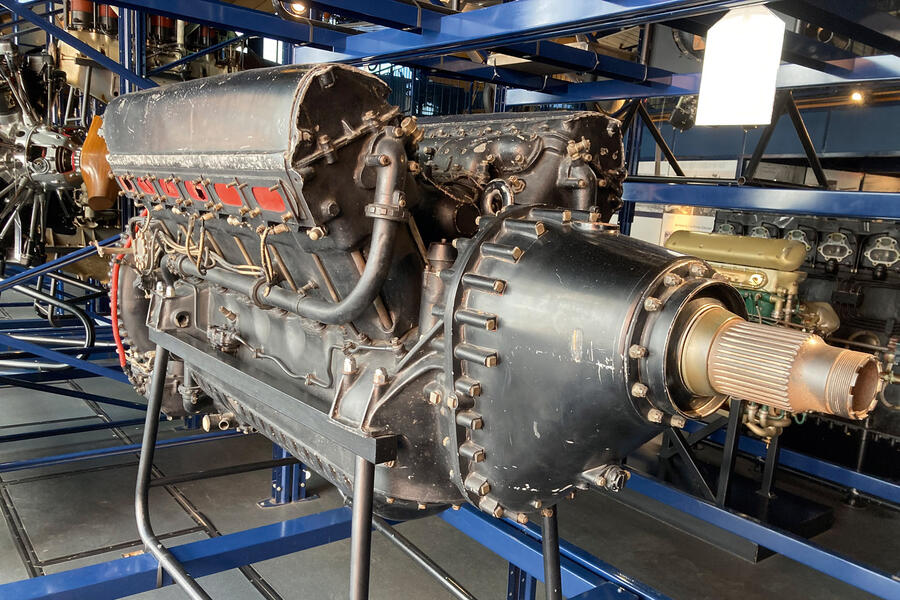

The first country to win the trophy three times in five years will keep it forever. Britain won it in 1927 and again in 1929, and now it stands to win it a third and final time, at least if the mighty supercharged 37-litre V12 Rolls-Royce ‘R’ engines powering our team’s Supermarine S.6Bs hold up.

The trouble is they are being tested to breaking point. They were used in the 1929 contest, when they produced 1800bhp and a winning speed of 328.64mph, but for the 1931 contest they’ve been boosted to 2350bhp. This has put a huge strain on them.

To avoid them self-destructing, Rolls-Royce advises that they are run for only a few hours before they must be returned to its Derby factory for dismantling, inspection and rebuilding using uprated parts.

However, 180 miles separates the company’s Osmaston Road site from RAF Calshot, on Calshot Spit beside the Solent in Hampshire, where the engines and the planes they power are being tested prior to the race in September. As the event draws near, every day counts. If the engines are to go to Derby, they must be back at Calshot and in the aircraft as soon as possible so that preparations can continue.

And then someone has an idea. For the greatest aero engines in the world, there can be only one means of transport: the greatest car in the world. That would be the Rolls-Royce New Phantom, otherwise known as the Phantom I.

Nobody can be sure whose idea this was, but my money is on one Aircraftman TE Shaw, aka Lawrence of Arabia. He was involved with the 1929 Schneider race and in 1931 was often at Calshot. He adored the New Phantom’s predecessor, the Silver Ghost, describing the armoured versions he drove in the desert as being “more valuable than rubies”.

Now, with time fast running out, I like to think that he reminded the Schneider team, as well as Rolls-Royce, that the engines should be rushed to Derby and back in nothing less than a New Phantom, just as the same engines had been in the run-up to the 1929 Schneider Trophy race.

Whatever the truth, a New Phantom limousine, fitted with the standard 7.7-litre straight six producing what Rolls-Royce coyly describes as “sufficient power”, is quickly procured from the manufacturer and converted into a lorry large enough to carry a single ‘R’ engine.

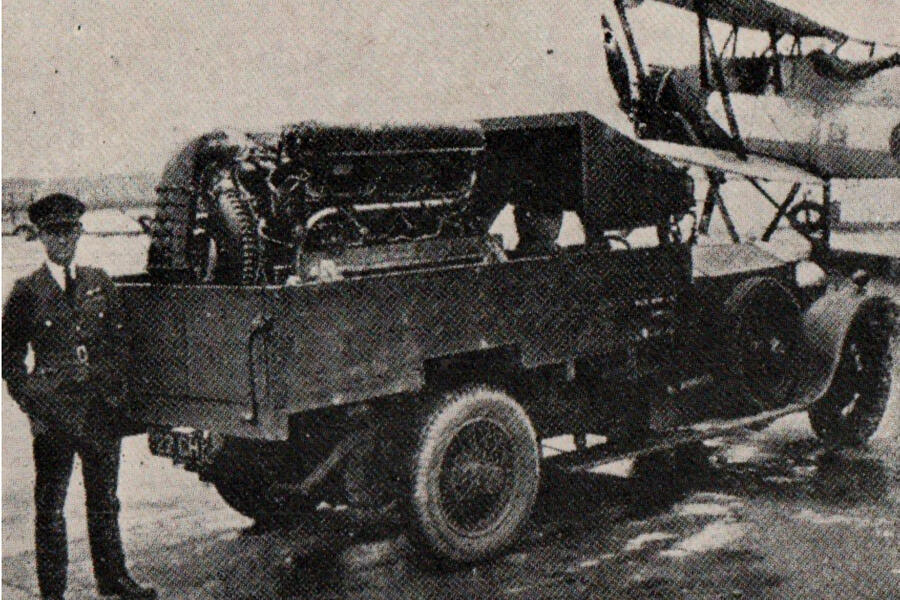

A rare photograph shows the improvised truck complete with its cargo. The engine, all 2.3 metres of it from propeller-shaft stub to coiled supercharger, dwarfs the load bed.

The engine is probably covered for the journey, but the crew are more exposed to the wind and rain of that wild English summer. There’s a roof of sorts above them, but it’s angled upwards, its primary purpose appearing to be to deflect the rain from the engine.

One thing’s for sure: if the Phantom truck is involved in a head-on smash, the V12 engine will take its last flight and the crew with it. Given that the only time the engines can be ferried to Derby is at night and probably in the rain, such an outcome is a distinct possibility.

The crew is under real pressure to complete the journey as quickly as possible on roads that we today would call B-roads, their path barely illuminated by their huge headlights. On at least one occasion, Hampshire Police catches the truck speeding at 80mph. No wonder it’s nicknamed the Phantom of the Night.

Forward to today, and how might the Calshot team transport their Rolls-Royce V12 aero engines to Derby at speed? If Lawrence were around to steer the discussion, I hope they would settle on the Phantom truck’s equivalent, the Rolls-Royce Cullinan Black Badge.

Some of the team might reasonably ask how a 37-litre aero engine would be coaxed through the split-folding tailgate and into the boot of this super-luxury SUV (or XUV, as Rolls-Royce has it), but these are the some of the world’s greatest problem-solvers – and in any case, once it’s there, I know it will just about fit.

The thing is, I’ve measured the ‘R’ engine on display at London’s Science Museum. It’s number 27, the one that powered Britain’s 1931 trophy-winning Supermarine S.6B number S1595 and which, two weeks later, took the same aircraft to a record-breaking average speed of 407.5mph.

Comparing my measurements of it with those I’ve taken of a Cullinan’s boot, I can confirm that only around 30cm of the 2.3m-long V12 (at least all of it being the propeller-shaft stub) will extend from the back of the car. Chuck in some suitable floor protection and the team has a safe, secure and practical all-weather SUV for high-speed engine deliveries. Now to try it…

Parked on my drive, the Cullinan makes my Volkswagen Golf look like a Volkswagen Polo. It’s enormous, although on opening the powered tailgate, I’m concerned by the presence of a large back box mounted on the floor of the boot, from which, at the push of a button, emerges two folding picnic chairs and a table.

It will have to go if I’m to get a record-breaking 37-litre aero engine in there. It weighs 744kg, but the Cullinan has four-wheel drive, uprated air suspension and huge brakes gripped by giant red calipers, so I’ve no concerns about the vehicle’s safety and stability.

Of course, even if the museum would allow me to borrow it, I’m not serious about stuffing the ‘R’ engine into the Cullinan, but I do want to take the car to Calshot and then try to follow what I believe is the route that the Schneider team would have taken to Derby in their Phantom of the Night 91 years ago.

I’ve plotted it with help from Google and the AA’s press officer, who sent me a link to a contemporary road map, although for photography purposes I will be journeying during the day.

All set, I press the starter button and, with the 6.75-litre V12 turning quietly somewhere ahead of me, progress sedately from my gravel driveway and down the road.

I’m at Calshot in a blink. The Royal Navy established an air station on the Spit in 1913 for maritime reconnaissance and weapons development. Only the Sopwith hangar remains from that time, later joined by the huge Sunderland Hangar (1917), now a popular activity centre, and the Schneider Hangar.

Opposite the Sunderland Hangar is Calshot Castle, a circular fortification built in the 16th century. Between them are the remains of the concrete ramp down which seaplanes, including the S.6Bs, would enter and leave the water.

There’s time, before I must be on my way, to take the Cullinan off road. In truth, ‘off road’ is just a level grassy area beside the beach where motorhomes park up, but it’s muddy and the mere fact of driving a Rolls-Royce on it seems preposterous enough for it to rank as daring. A button labelled ‘Off Road’ reminds me that this car does have the chops for something more challenging.

Securely back on Tarmac and my re-enactment of its predecessor’s historic sprints to and from Derby begins. Although I doubt such things bothered the Phantom’s hardy crew, I have no concerns about my comfort or safety. I will have to keep my eye on the speedometer in the Cullinan’s head-up display, though. From the strain of its engine and the wind in his face, the Phantom’s driver must have known that he was 20mph short of doing a ton through Hampshire, whereas I, insulated from reality by the Cullinan’s double-glazing, noise-muffling tyres and silky-smooth 591bhp V12, am blissfully ignorant.

I wonder if he ever stopped to refuel? The Cullinan is returning around 13mpg, and that’s with a reasonably careful right foot (there’s the occasional lapse while I remind myself what 0-62mph in a claimed 4.9sec feels like in a 2700kg SUV). At one point, with 25 miles in reserve, I fill up with super unleaded, as the factory advises. The bill: £160.

Via various A- and B-roads, all comfortably and expertly dispatched by the Cullinan, I arrive at Osmaston Road at around 7pm. The sat-nav has brought me to a locked set of gates outside the former site of the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust, custodian of the firm’s aeronautical and motoring history (it permanently closed quite recently, but I hear there are plans to relocate the collection elsewhere).

As commuters head home nearby, I try to summon up the image of the Phantom truck with its precious cargo being quickly waved through the gates and rushed to an expectant team of engineers ready to strip, inspect and rebuild it in time for its return journey the next day.

With the Schneider Trophy in the balance and a sceptical British government looking on, they must have been under huge pressure to get it performing reliably at maximum boost. At least they could rely on one thing: the Phantom of the Night and its dedicated crew.

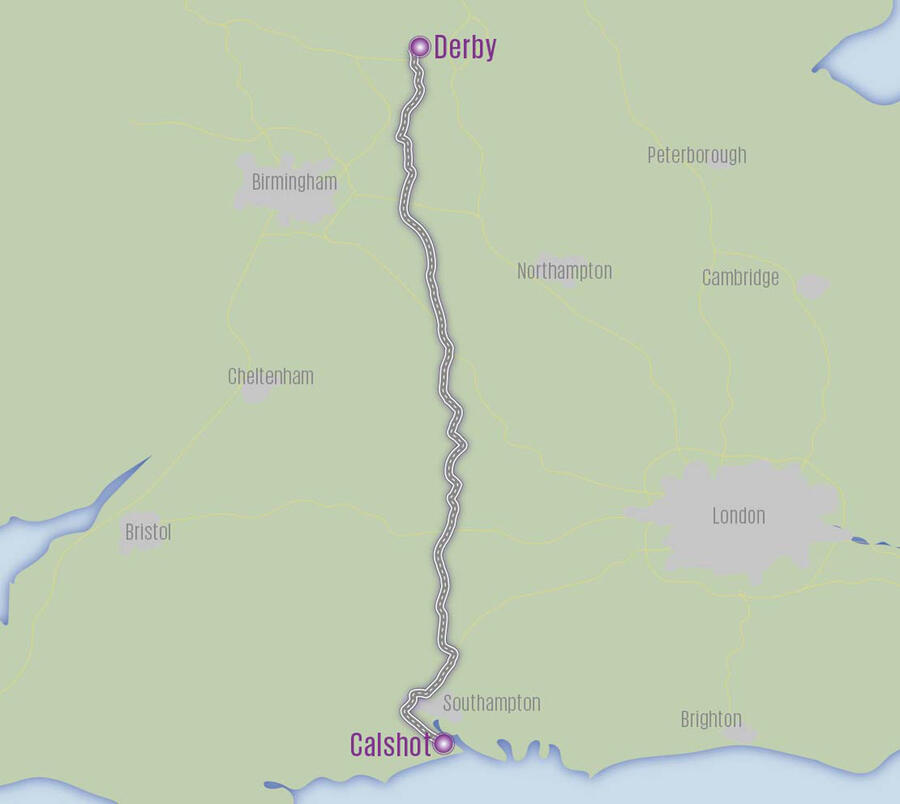

Reconstructing the route

Sources say only that the Phantom truck went from Calshot to Derby, so I had to guess the route it might have taken. Obviously, it had to be the quickest and most direct one. So armed with Google Maps and a contemporary Ministry of Transport road map sent by the AA, I plotted what I believed to be the likeliest.

The only conscious deviation I made was taking the M27 and M3 to Winchester before starting the route proper, north of the city at the A34. When the Rolls-Royce crew made the journey, roads were much quieter and this route avoided the crush of modern Southampton’s daytime traffic and urban speed controls.

The 174-mile route that I plotted was pleasingly direct. Minus stops for photography, lunch and refuelling, the journey took me four hours.

The Schneider Trophy

The Schneider Trophy was founded in 1912 by French engineer and financier Jacques Schneider to encourage aviation development.

Exclusively for seaplanes, it had by 1931 been contested 11 times by teams from Britain, France, Italy and the US, with each winning country hosting the next race. The team that won the trophy three times within five years would be allowed to keep it.

By the time of the 1931 race, Britain’s prospects of winning the trophy for the third time in the qualifying period weren’t looking good. The government, battling an economic crisis, had withdrawn its financial support, but Lady Houston, a wealthy philanthropist and fervent patriot, gave the British team £100,000 (about £5 million in today’s money) to ensure that the bid could go ahead.

More good news followed when France and Italy pulled out (the US had quit back in 1926), leaving the British team free to attempt to beat their 1929 race-winning speed of 328.64mph.

Happily, they did, achieving 340.08mph around the 220-mile triangular course over the Solent. The trophy is now displayed at the Science Museum in London.

How racing helped win the war

If the Schneider Trophy was intended to encourage developments in aero engines, then in the case of the supercharged 37-litre V12 Rolls-Royce ‘R’ engines that powered Britain’s winning planes of 1929 and 1931, it succeeded more than anyone could ever have imagined.

The need to extract ever greater performance from them led to huge improvements in design, quality and reliability in a short space of time that would otherwise never have been made.

Ultimately, much of this knowledge and experience helped inform the design of the legendary Rolls-Royce Merlin V12 engine that powered Britain’s Supermarine Spitfire fighter plane in World War II.

The experience of high-speed flight that Supermarine’s RJ Mitchell gained from his design of the Schneider race planes influenced much of his work on the same aircraft.